Today's Noonday Prayer service focuses on the first woman hymnwriter and poet of the Protestant Reformation, Elisabeth Cruciger. Learn more here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bkfMH9zaBto

0 Comments

Of the four Gospels, Mark's is the earliest, the shortest, and the one in which Jesus is always on the move. In this painting by Guiseppe Caletti, you can see the lion on the right, very interested in what Mark is doing. Each of the Evangelists has a symbol; the lion is Mark's. To learn what little we know (or think we know) about him, here is the Noonday Prayer service for April 25, his feast day. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nk6m-9EyETI  This remarkable nineteenth-century Brahmin woman was an advocate for Indian women. Learn more about her in this Noonday Prayer service, with my apologies for the fuzzy feed. It clears around 5 minutes and gets a little fuzzy again later. If it bothers you, you can always just listen--pretend its a podcast! http://christspringfield.org/thursday-online-noonday-prayer-service/ These are the opening words of Catherine of Siena’s The Dialogue: “A soul rises up, restless with tremendous desire for God’s honor and the salvation of souls. She has for some time exercised herself in virtue and has become accustomed to dwelling in the cell of self-knowledge in order to know better God’s goodness toward her, since upon knowledge follows love. And loving, she seeks to pursue truth and clothe herself in it.”

Catherine of Siena terrified me with her passionate pursuit of justice, her extroversion and willingness to confront people. Jesus called her out of her private room of contemplation, and that struck terror in my soul. I was in my second term of seminary, in that same class where I’d discovered Julian, and all I wanted was to sit in a room and watch the sun move along the white walls of my apartment. Just me and Jesus and all the textbooks, the classes, research papers and projects, the libraries. Quiet and time to think. Fearing God would not allow me to have that life, uncertain about what came next, I stretched my two-year program into three years, taking classes that didn’t fit my area of concentration but piqued my interest. I traveled to a conference in Kentucky to present a workshop that reflected my independent research on a Methodist deaconess and missionary (originally from Ohio!), Isabella Thoburn. I tried for a doctoral program that would combine my interests in church history and women, but one school had closed their program and another had 44 applicants for 4 slots and did not find my research worthy. I talked with a marvelous professor in Chicago, who suggested if I wanted to pursue a PhD in medieval women and church history, I’d need to know medieval French and German. He told me some people took a year off just to do language studies. I talked to PhD women students, welcoming and honest, one of whom was doing doctoral research on Isabella Thoburn; she told me about her trip to India to see Isabella's grave and the women's college she founded. And I grew progressively more discouraged. My mother was not well; I didn’t want to be across the country if she needed me. I’d already achieved an impressive level of debt for a degree I knew all along would not lead to a job. I was encouraged to try for the directorship at my seminary, but I didn’t want it. I interviewed for a position at a nearby college library, but I frightened them with my interest in religion. I had no job and no clarity when I did graduate. I mved back to the Miami Valley, encouraged by a library worker who told me that the spider weaving a web always went back to the center to begin again. That autumn, I stumbled into editing through the kindness of a friend. I wasn't going to be able to sit in a room and think deep thoughts. |

Saints Alive!

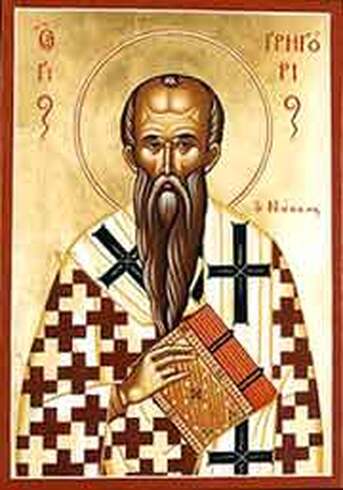

I have been privileged to offer Noonday Prayer at my church, usually on Thursdays, which doesn’t matter because it’s on Youtube forever. [It’s amazing what can be done with a smartphone and a smart, helpful parish administrator!] The service is brief, with a place for a meditation. We usually look at the Episcopal calendar of saints, who are nearly always honored on their death dates, not their birth dates. Here is a hymn by medieval saint Hildegard of Bingen to set the mood.

Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed